A plaque at Mills Place could be updated to provide information on a violent, racially motivated incident that occurred nearly 135 years ago that forced Chinese residents to flee for their lives and destroyed the city’s burgeoning Chinese business district.

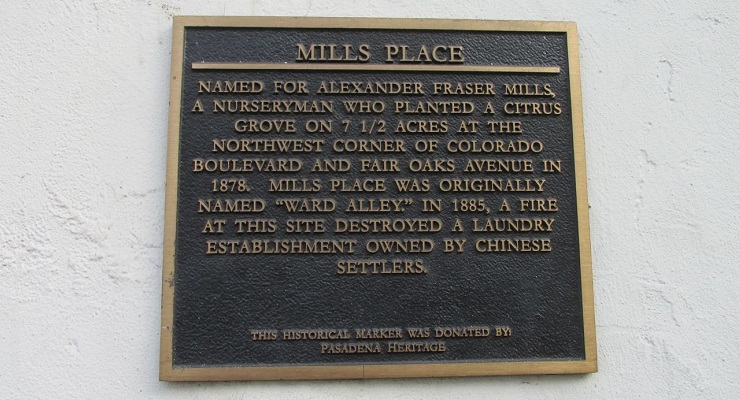

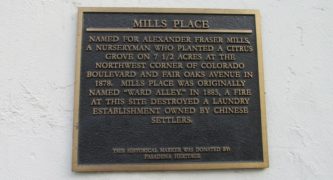

Today, a plaque at Mills Place and Green Street in Old Pasadena currently reads “Named for Alexander Fraser Mills, a nursery man who planted a citrus gover on 7 ½ acres at the Northwest corner of Colorado Boulevard and Fair Oaks Avenue in 1878.

Mills Place was originally named Ward Alley in 1885. A fire at this site destroyed a laundry owned by Chinese settlers.”

The plaque is one of more than 40 historical markers that pay homage to Pasadena’s earliest settlers, merchants and businesses. Some of Old Pasadena’s 22 alleys have more than one of the 9 x 12-inch markers, according to the city’s website.

However, two Pasadena residents who know of the story recently notified City Councilmember Felicia Williams that this description does not capture the gravity of the events connected to the fire.

“A constituent brought this to our attention along with important historical information on the ‘Night of Terror’ incident,” Williams told Pasadena Now on Wednesday.

“Staff saw the importance and urgency for accurate information on our history so we don’t repeat it in the future, and I look forward to seeing this move forward through the public process,” Williams said.

According to a memo by LaWayne Williams, the city’s recreation and community services superintendent, the matter is being brought to the Human Relations Commission for ways to address the inaccuracies on the plaques, the memo said.

Recommendations could include, but are not limited to:

• Creating new plaques solely dedicated to acknowledging this event.

• Hosting a public event to educate the public about the atrocious events from that time.

• Working with city staff to initiate a press release.

The fire, which occurred in 1885, according to a 2015 Pasadena Weekly article by Matt Hormann, was caused by a white mob “that turned Pasadena’s Chinatown into an inferno, obliterating it from the landscape, and, for many years, from the history books as well.”

Over the course of 24 hours, “enraged racists drove Pasadena’s 60 to 100 Chinese citizens from the city in an ordeal that began with a dropped cigar and culminated in threats of a mass lynching,” the article recounts.

“Roughly 100 men — nearly one-quarter of the population of Pasadena — participated in the riot, yet no one was ever arrested or charged in the case. To this day, the rioters’ names remain unknown,” Hormann’s article reads.

The incident led to the formation of the city’s fire department and decades of racial separation, according to the article.

In 1883, Yuen Kee moved his laundry, which was the first Chinese owned business in Pasadena, to Mills Place (then called Mills Street), in present-day Old Pasadena, where he rented a 544 square-foot building from Jacob Hisey, a trustee of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church.

Soon, other Chinese entrepreneurs were doing business on Mills Street, but trouble followed.

According to Hormann’s article, in 1884 the Pasadena & Valley Union, the city’s only newspaper, began publishing racist articles that called the Chinese “an objectionable class” whose immigration “ought to be restricted.”

Later that year, the paper claimed there was “sufficient cause” for expelling the Chinese from Pasadena and claimed it could be done legally.

It wasn’t long before nearly 100 men had signed a petition pledging not to lease property to Chinese people. The paper continued to fuel the racist fire by claiming the agreement must be effective in driving them out if all property owners would unite in it.

It was signed by future mayors M.H. Weight and T.P. Lukens, the city postmaster, the local justice of the peace, the president of the Colorado Street Railroad Co., and the man who laid the cornerstone for Castle Green.

A fire began the same day that the names were revealed. Though it was quickly extinguished, the city was on edge and a group of white men gathered near the laundry.

After the men began throwing rocks, a lamp was knocked over and the fire began. In full mob mentality, the men began looting the laundry after the Chinese residents fled for their lives.

The day after the fire, the Chinese residents returned to find an effigy of a Chinese man had been lynched from a telegraph pole across the street. Sadly, at the same time city officials were drafting a racist ordinance.

“That it is the sentiment of this community that no Chinese quarters be allowed within the following limits of Pasadena: Orange Grove and Lake avenues, California St. and Mountain Avenue,” the ordinance reads.

Chinese were warned to leave the city within 24 hours or they would “call out the crowd, and they would run the Chinese out by force.”

Fearing for their lives, Pasadena’s Chinese residents left town, Hormann’s story states.

“When I researched the article in 2014-15, my main intention was simply to tell the story of what happened,” Hormann told Pasadena Now. “I thought it might also spur the city to correct the plaques, but no one seemed interested at the time. However, changes like these often need a historical moment to gain momentum. In the past year, we’ve had an incredible reckoning with our country’s racist past, starting with the George Floyd protests and Confederate statues being removed, and culminating with the Stop Asian Hate campaign and new awareness of the history of anti-Asian racism. It’s an ideal moment to grapple with our own city’s history, and figure out better ways to move forward.”

Hormann called the proposals by the Human Relations Commission a “terrific start,” but added ongoing public education measures should be included.

“It would also be nice to see a memorial to the Chinese themselves, highlighting their contributions to the community, so that their history isn’t just encapsulated by a senseless tragedy,” Hormann said.

“They literally crossed an ocean to get here, heavily indebted to the steamship companies that brought them, and were indispensible to the founding of the city,” he continued. “Before the many restrictions on Chinese immigration, they were the primary labor force on most local ranches, and made men like Alexander Mills rich beyond measure. Yet, their names are erased, while the names of the wealthy magnates they worked for live on.”

One thought on “City Considering Ways to Correct Historical Omission of ‘Night of Terror’ Against Local Chinese Residents”

Thank you for your news report on this important piece of local history. We all regret the racial bias and systemic discrimination of our shared past. The question remains: what shall we do together to move forward? Let’s apologize, take down this unfortunate plaque, and build more accuracy. The plaque is only held by a few screws; remove it now.