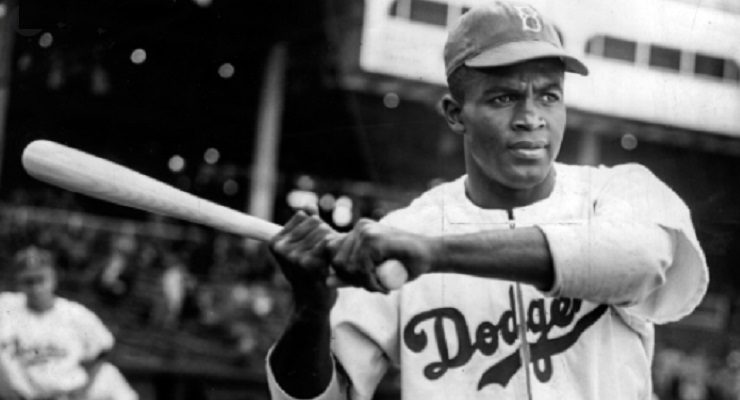

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier when he took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers. To honor Robinson, Major League Baseball has designated April 15 as Jackie Robinson Day. On that day each year, every player, coach, manager and umpire in Major League Baseball wears Robinson’s uniform number, 42. This year is special because it marks the 75th anniversary of that transformative moment.

Pasadena has a Jackie Robinson Park, a Jackie Robinson Center, and huge busts of Jackie and his older brother, Mack, in front of City Hall. But while Baltimore has a museum to honor Babe Ruth and Royston, Georgia has one for Ty Cobb, Pasadena has no museum where Pasadena residents and tourists can learn about Jackie’s upbringing, his struggle against segregation as an Army officer in World War II, his brief career in the Negro Leagues, his odyssey as a sports pioneer and civil rights activist, and the protest movement that paved the way for Robinson’s achievements.

Thanks to the persistence of Jackie’s widow, Rachel, the official Jackie Robinson Museum will soon open in New York City. But that’s no excuse for Pasadena not to provide opportunities for current and future generations of Pasadenans to learn about this American icon and the struggles he and others engaged in to fight racism in Pasadena and around the country. It is time for PUSD to fully incorporate the Robinson story into its curriculum, from elementary school through high school.

§

The grandson of a slave and the son of a sharecropper, Robinson was 14 months old in 1920 when his mother moved her five children from Cairo, Georgia, to Pasadena. In Jackie’s youth, Pasadena’s Black residents (five percent of the city in 1940) were treated like second-class citizens. Its movie theaters and municipal pool were segregated. Blacks faced constant harassment from local police. Pasadena had no Black firefighters or policers. After his mother Mallie purchased a house 121 Pepper Street in 1922, in what was then a white neighborhood, neighbors burned a cross on the front yard.

When Mack (1914-2000) returned from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, where he won the silver medal in the 200-meter race (finishing fourth-tenths of a second behind Jesse Owens), he was not welcomed back as a local celebrity. “I looked forward to a hero’s welcome,” Mack recalled, “but the family greeted me and that was basically it.” In 1937, Mack set a national junior college record in the broad jump (later broken by Jackie) and he won national collegiate and Amateur Athletic Union track titles at the University of Oregon the next year. But despite the fact that he had attended college and was a well-known athlete, the only job Mack could get when he returned to Pasadena was cleaning the city’s streets and sewers.

In the 1940s, Mack joined an effort to push the city to desegregate the public swimming pool at Brookside Park (which was only open to Black residents once a week, just before the water was changed). In 1944, after a judge ordered local officials to desegregate the pool, the city retaliated by firing its few Black employees, including Mack. He later became a truant officer at Muir High and fought to get the city to sponsor youth programs.

A star athlete at Muir High School and Pasadena Junior College (now PCC), Jackie transferred to UCLA, where he became its first four-sport athlete (football, basketball, track, and baseball), twice led basketball’s Pacific Coast League in scoring, won the NCAA broad jump championship, and became an All-American football player. Many consider him America’s greatest all-around athlete.

During World War II, Jackie confronted racism when his superiors sought to keep him out of officer’s candidate school. He eventually broke that barrier and became a second lieutenant. But in 1944, while assigned to a training camp at Fort Hood in segregated Texas, he refused to move to the back of an army bus when the white driver ordered him to do so, even though buses had been officially desegregated on military bases. Robinson faced trumped-up charges of insubordination, disturbing the peace, drunkenness, conduct unbecoming an officer, and refusing to obey the orders of a superior officer. Unlike the routine mistreatment of many Black soldiers in the Jim Crow military, however, Robinson’s court-martial trial, on August 2, 1944, triggered stories in Black newspapers and protests by the NAACP because he was a well-known athlete. Voting by secret ballot, the nine military judges (only one of them Black) found Robinson not guilty. In November, he was honorably discharged from the Army.

Describing the ordeal, Robinson later wrote, “It was a small victory, for I had learned that I was in two wars, one against the foreign enemy, the other against prejudice at home.”

After his military service, Jackie was barred from playing in the all-white major leagues. Instead, he played for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues. In 1945, Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, selected Robinson to break the color barrier, not only because he was an outstanding player, but also because he was well-educated, religious, articulate, an army veteran, and had lived among and played with white teammates in Pasadena and at UCLA. After a year with the Dodgers’ minor league team in Montreal, Robinson first took the field in a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform on April 15, 1947.

§

Robinson’s actions on and off the diamond paved the way for America to confront its racial hypocrisy. His dignity in handling ugly physical and verbal abuse among fellow players and fans, and persistent racism in hotels and restaurants, stirred white Americans’ consciences and gave Black Americans a tremendous boost of pride.

Many Americans viewed his achievement as a steppingstone to tearing down other forms of racism. His efforts were as important as the Supreme Court’s 1954 school desegregation decision or the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott in dismantling legal segregation. Rev. Martin Luther King said that Robinson “underwent the trauma and the humiliation and the loneliness which comes with being a pilgrim walking the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the Freedom Rides.”

During his playing days — 1947 to 1956, all with the Brooklyn Dodgers — Robinson had a .311 lifetime batting average and led the Dodgers to six pennants. He was Rookie of the Year in 1947, Most Valuable Player in 1949, and elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962.

The battle to end baseball’s Jim Crow system is often told as the tale of two trailblazers — Robinson, the combative athlete and Dodgers president Branch Rickey, the shrewd strategist — battling baseball’s, and society’s, bigotry. But the truth is that it was a political victory brought about by a progressive protest movement.

Starting in the early 1930s – when Jackie was still a teenager — a broad coalition that included Black newspapers, civil rights groups, radical politicians, and left-wing labor unions waged a sustained campaign to dismantle baseball’s color line. They published open letters to baseball owners, wrote stories about Negro League teams beating teams of outstanding major leaguers in exhibition games, polled white managers and players about their willingness to have Black players on major league rosters, picketed at baseball stadiums in New York and Chicago, gathered signatures on petitions, put pressure on owners, and kept the issue before the public. It was part of a broader movement to eliminate discrimination in housing, jobs, and other sectors of society.

In 1942, sportswriters for Black papers and the radical Daily Worker newspaper sent telegrams to team owners asking them to give tryouts to Black players. The Chicago White Sox reluctantly invited Robinson and Nate Moreland (another Pasadena resident) to a tryout on March 19 at Pasadena’s Brookside Park, where the team held spring training. Manager Jimmy Dykes raved about Robinson: “He’s worth $50,000 of anybody’s money. He stole everything but my infielders’ gloves.” But neither ballplayer ever heard from the White Sox again.

Robinson recognized that the dismantling of baseball’s color line was a triumph of both a man and a movement. He repaid that debt through his deep involvement in the civil rights movement during and after his playing days. He viewed his celebrity as a platform from which to challenge American racism. He frequently spoke out — in speeches, interviews, and his newspaper columns — against racial injustice. In 1949, testifying before Congress, he said: “I’m not fooled because I’ve had a chance open to very few Negro Americans.” Many white sportswriters and most other players — including some of his fellow Black players, content simply to be playing in the majors — considered Robinson too angry and vocal about racism in baseball and society.

When Robinson retired from baseball in 1956, no team offered him a position as a coach, manager or executive. Instead, he became a vice president with the Chock Full o’ Nuts restaurant chain and intensified his civil rights activism. He was a constant presence at civil rights rallies and picket lines. He chaired the NAACP’s fundraising drive but also raised money for Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He used his regular columns for the New York Post and the New York Amsterdam News (a Black weekly) to support the student sit-ins at Southern lunch counters, the Freedom Riders, and the voter registration drives.

§

Robinson was proud of his accomplishments on the baseball field and in society, but he was frustrated by the slow pace of racial change in baseball and society.

“I cannot possibly believe,” he wrote in his autobiography I Never Had It Made, published shortly before he died of a heart attack at age 53 in 1972, “that I have it made while so many black brothers and sisters are hungry, inadequately housed, insufficiently clothed, denied their dignity as they live in slums or barely exist on welfare.” Years before Colin Kaepernick was born, Robinson wrote: “I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.”

Jackie was bitter about Pasadena’s segregated schools and public facilities and mistreatment of its Black residents. He and Rachel rarely visited the city after they moved to the East Coast when Jackie joined the Dodgers. During his lifetime, Pasadena did little to honor its most famous son. For example, Jackie was never invited to serve as the Rose Parade’s grand marshal. Rather than preserve the family’s Pepper Street house as an historic site and perhaps even a museum, the city allowed the home to be torn down in the 1970s, replaced by another house. Only a small hard-to-find plaque on the sidewalk identifies the site as the one-time home of Pasadena’s greatest citizen.

Today, Pasadena prides itself as a diverse city with an international profile. Whatever racial progress the city has made since Robinson grew up here is due in large measure to the efforts of civil rights activists (including Mack Robinson and his wife, Delano) and their allies. But Pasadena still confronts a wide economic divide and persistent racial inequality.

How can we honor Robinson’s legacy and learn the lessons of his remarkable life? PUSD and surrounding school districts should incorporate the Robinson saga into their core curriculum as a way to teach about the history of race relations and the ongoing struggle for social justice.

Peter Dreier, a Pasadena resident, is professor of politics at Occidental College and co-author of two new books, “Baseball Rebels: The Players, People, and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America” and “Major League Rebels: Baseball Battles Over Workers’ Rights and American Empire.” He will be discussing those books at a virtual event sponsored by Vroman’s Bookstore on Tuesday, April 19 at 6 pm. Register at: https://www.crowdcast.io/e/peter-dreier