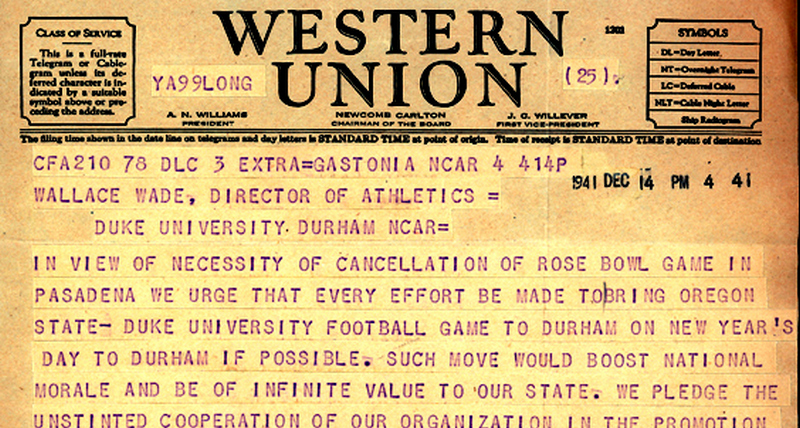

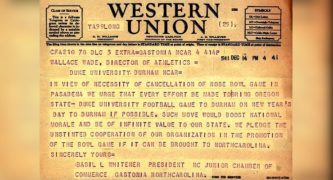

Telegram from 1942 Rose Bowl explaining why the move happened from North Carolina Chamber of Commerce Basil Whitener. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

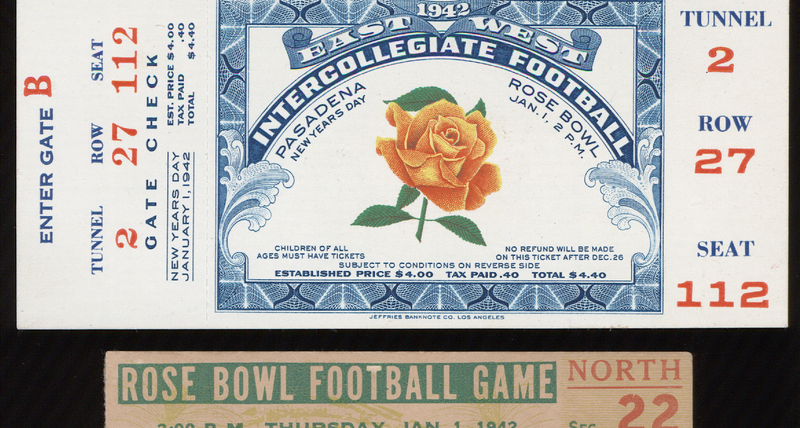

Top: Original game ticket from the 1942 Rose Bowl, when it was supposed to be played in Pasadena. Bottom: Rose Bowl Football Game Ticket from North Carolina. The total price of a ticket was $4.40 (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

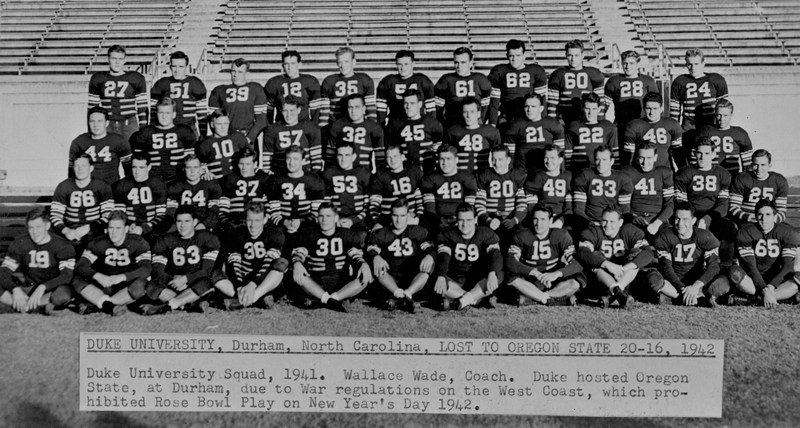

Duke University Squad, 1941. Wallace Wade, Coach. Duke hosted Oregon State, at Durham, due to War regulations on the West Coast, which prohibited Rose Bowl Play on New Year's Day 1942. (Photo Courtesy of Pasadena Tournament of Roses Archives.)

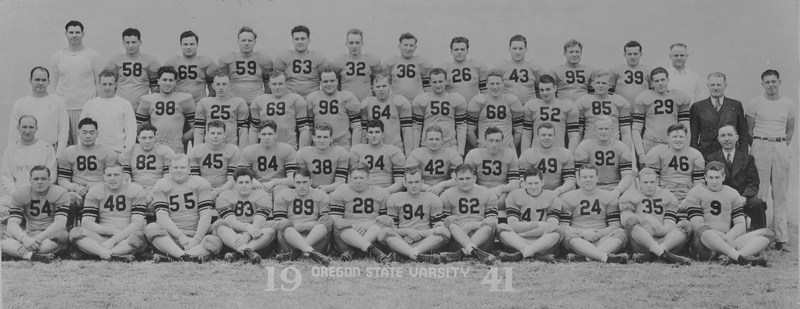

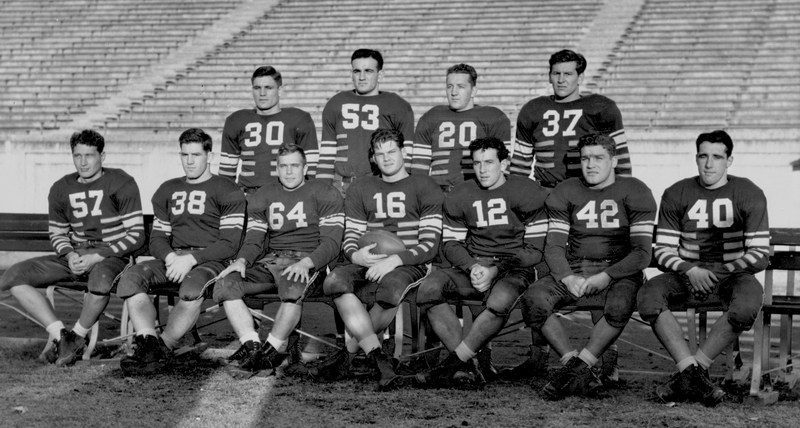

Oregon State University 1942 Varsity Football Team, who played in the 1942 Rose Bowl in Dunham, NC. (Photo Courtesy of Pasadena Tournament of Roses Archives.)

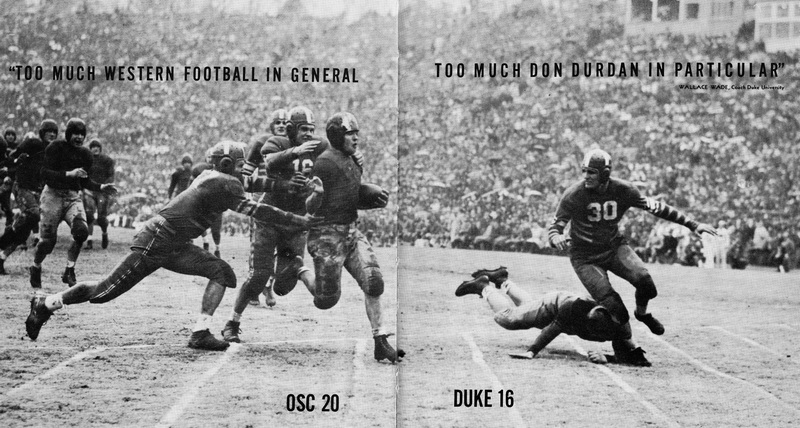

"Too Much Western Football in General, Too Much Don Durdan in Particular" Wallace Wade, Coach Duke University. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

Original School Flags from the 1942 Rose Bowl Game. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

A group of students getting on a train to the 1942 Rose Bowl in Durham, North Carolina (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

1942 Duke Team. (Photo Courtesy of Pasadena Tournament of Roses Archives.)

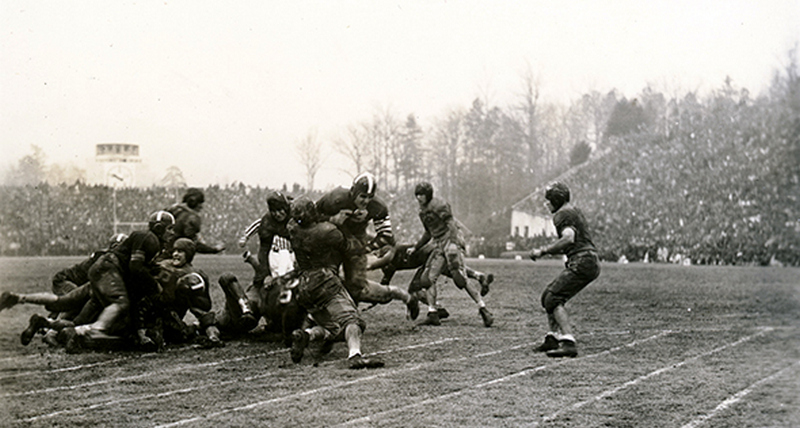

Duke University and Oregon State University battle against each other in the 1942 Rose Bowl. (Photo Courtesy of Pasadena Tournament of Roses Archives.)

1942 Rose Bowl Player of the Game Don Durdan of Oregon State University. (Photo Courtesy of Pasadena Tournament of Roses Archives.)

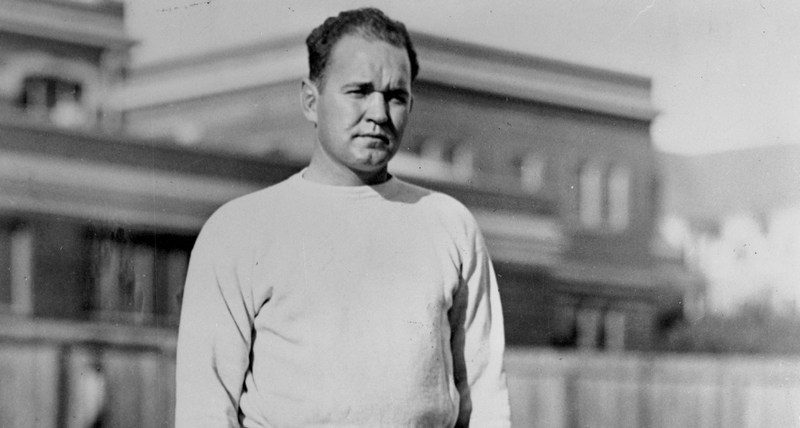

Oregon State Coach Lon Stiner. (Photo Courtesy of Pasadena Tournament of Roses Archives.)

The crowd at the 1942 Rose Bowl Game. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

Duke University and Oregon State University battle against each other in the 1942 Rose Bowl. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

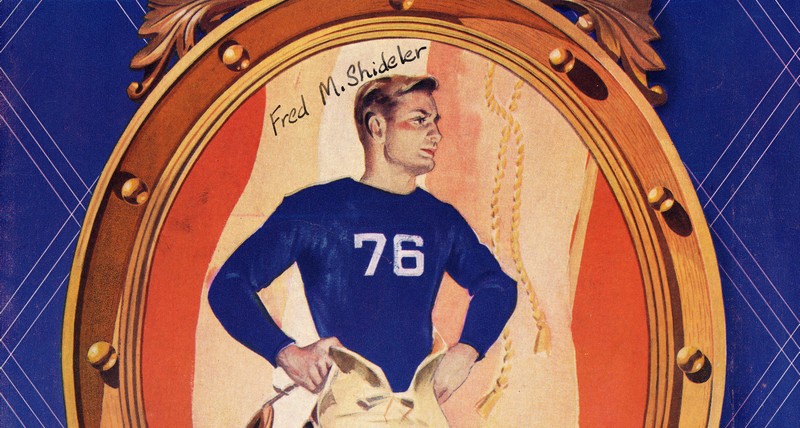

Program Cover from the 1942 Rose Bowl. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

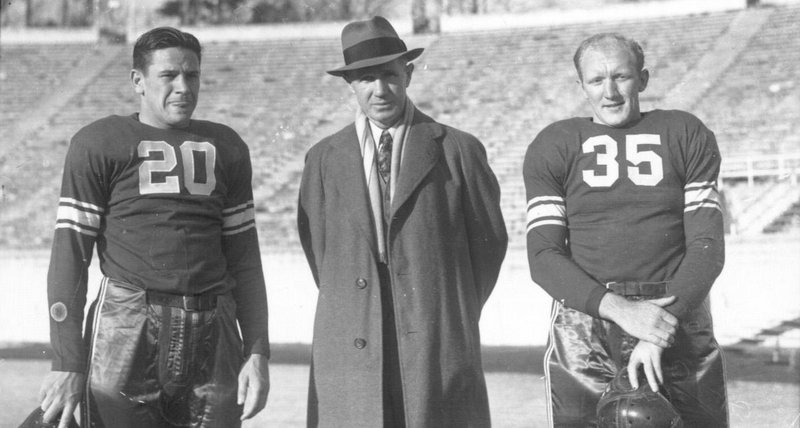

Duke Coach Wallace Wade standing with two football players. (Photo Courtesy of Duke University via Twitter.)

The 1942 Rose Bowl Trophy. (Photo Courtesy of Oregon State University Archives.)

The coronavirus pandemic can lay claim to many tragic once-in-a-lifetime events in the modern era: infecting and killing untold millions worldwide; the indefinite shuttering of churches, government offices, newspapers, businesses, theaters, bars, restaurants, libraries, even courts; the closure of schools and the transformation of education at all levels; the imposition of stay-at-home orders and curfews; and the steamrolling of lives, relationships and careers in its way to causing even more global death, destruction and disruption.

In many ways, it could be argued the battle against the COVID-19 is much like fighting a world war.

One local collateral cultural casualty of the struggle against the virus is the Rose Parade, which was canceled earlier this year, with a quickly assembled and well-produced television special taking its place on New Year’s morning.

Another is now the Rose Bowl Game, which up until last week was slated to feature one of college football’s two semi-final championship games on Jan. 1.

Those hopes were dashed on Dec. 18, when the organization known as the College Football Playoff (CFP) decided the game needed to have family members of team members and some fans in the stands, which California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s stay-at-home order does not allow.

So, as a result, and as odd as it may seem to some, this year’s game has been moved, with the showdown between No. 1 Alabama and No. 4 Notre Dame now set to be played in AT&T Stadium in Texas, a state in which a significantly reduced number of fans are permitted to sit in the stands at sporting events as long as they adhere to COVID-19 protocols.

For the game in Arlington, an estimated 16,000 people, according to a report in the Los Angeles Daily News, will be allowed into AT&T Stadium, which seats 80,000.

As of this writing, it was still not known whether the city of Pasadena and the Tournament of Roses Association, which have proprietary rights to the name Rose Bowl Game, will allow the use of that name for the semi-final championship game in Texas. The City Council and tournament officials met in a special closed session earlier this week to discuss the matter, with no resolution announced.

Unforgettable Moment

A scenario much like the one described above played out in December 1941, following Japan’s aerial attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, President Franklin Roosevelt was warning of a potential second strike along the West Coast, which prompted the cancellation of the parade and the game.

But unlike the wartime Rose Parade, which couldn’t relocate hundreds of people, floats, bands, and equestrian acts somewhere further inland on just a few days notice, the Rose Bowl Game could be played elsewhere, and was.

On New Year’s Day 1942, less than a month after Pearl Harbor, the game went on at Duke University, featuring the formidable Duke Blue Devils and the Oregon State Beavers.

Up to this point, this was the only time the Rose Bowl Game, the oldest of the nation’s bowl games, first played in 1902, with the annual tradition beginning in 1916, had ever been played outside of Pasadena.

Accepting an invitation to play by Duke Coach Wallace Wade, the Oregon State football team, Pacific Coast conference champions that year, boarded a train in Corvallis for the nearly 3,000-mile trip to Durham.

Andy Landforce, a 1942 Oregon State graduate and football team member, recalled the importance of being able to play the game.

“Coach Wade from Duke University called [Oregon State Coach] Lon Stiner and asked him, ‘If you want to play the game would you be willing to come back here?’ Everybody was enthused because this is a moment in life that you’ll never forget — to play in a Rose Bowl,” Landforce said in a video about the game made by Oregon State.

In an ironic twist, Wade, no stranger to Pasadena, started his college coaching career at Alabama, leading the Crimson Tide to three national championships in seven years, finishing the 1925, 1926, and 1930 seasons with two Rose Bowl victories and one tie in 1927 in the game against Stanford.

Wade left Alabama in 1931 with a record of 61 victories, 13 losses, and 3 ties, according to bleacherreport.com, owned by Turner Broadcasting System. He coached the Duke Blue Devils from 1931 through 1941, and again from 1946 to 1950.

In those intervening years, Wade, by now 49 years old, along with many of his student athletes, enlisted in the military. Starting out as a foot soldier but soon promoted to lieutenant colonel, Wade led the 272nd Field Artillery Battalion in the Battle of Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge. He was awarded the Bronze Star, four battle stars and was honored by the French government with the Croix De Guerre “Cross of War,” a high honor for heroism.

Wade’s career record as a head coach was 171-49-10, recording three national championships (all at Alabama) and 10 Southern conference championships (three at Alabama, seven at Duke).

Color Blind

While head coach at Duke, Wade was involved in the racial integration of college football. A native Southerner, he coached in segregated college programs, but had no problems with playing against racially integrated teams. In fact, he went out of his way to compete against those teams with Black players.

As a player at Brown University, Wade played alongside Fritz Pollard, one of the first African-American college players. They played together in a 14 to 0 losing effort against Washington State in the 1916 Rose Bowl, according to the Bleacher Report and the Tournament of Roses website.

In 1938, Wade led Duke against Syracuse and insisted the Orangemen play their best players, regardless of their skin color. He wanted his team to play against the best competition the opposition had to offer, whereas other coaches had requested that Syracuse not allow their Black players to take the field against their all-white teams.

Wade also invited the integrated University of Pittsburgh Panthers to play in Durham while other colleges refused to do the same. They played their game in 1950 without incident, according to Bleacher Report.

In the Rose Bowl Game of 1942, players were forced to perform in the rain on a muddy field, with some 55,000 drenched fans showing up to watch. Demand for tickets was apparently so great that Duke needed to borrow bleachers from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University to squeeze all the spectators into the stadium, according to Duke Today (today.duke.edu).

Even though Duke was favored to win, Oregon State scored 13 points in the third quarter to win the game by a score of 20 to16.

‘A Different Battle’

The weather and location were not the only reminders that this was a unique Rose Bowl. Duke officials, according to a story about the game appearing in Duke Today, had to receive clearance from authorities in Washington, D.C. for a plane to fly overhead to take pictures of the stadium, which the public-address announcer informed the crowd about beforehand so people wouldn’t think there was an attack under way.

Coach Wade, who died in Durham in 1986 at the age of 94, enlisted shortly after the Rose Bowl Game loss in Durham.

“My boys were going in (the military), and I felt like we should stay together as a team,” Wade told his biographer, Lewis Bowling. “We were just participating in a different battle.”

The 1942 Rose Bowl Game, states a story appearing in Sports Illustrated (si.com) simply had to be played, “not only because it prepared the men who participated in it for the hardships that awaited them in the Pacific and in Europe, but because it symbolized the determination and sacrifice and camaraderie that would define the American war effort.”

As former Duke player Jim Smith put it in a postwar interview, “[The Rose Bowl] gave people something to hang on to: We’re still a nation, we’re still here, we’re still going about things. That’s what sports can do.”

8 comments

8 comments