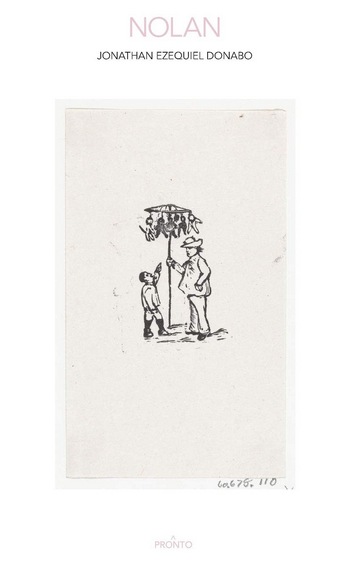

Nolan is a Mexican kid from LA. The Nolan poems chronicle his journey across Southern California and Mexico. Jonathan Ezequiel Donabo builds a world in magical realism to explore family, identity, and death through a coming of age story for a boy in the system.

Nolan is a Mexican kid from LA. The Nolan poems chronicle his journey across Southern California and Mexico. Jonathan Ezequiel Donabo builds a world in magical realism to explore family, identity, and death through a coming of age story for a boy in the system.

Released on July 1, 2020 from indie press Pronto, Nolan is now available wherever books are sold.

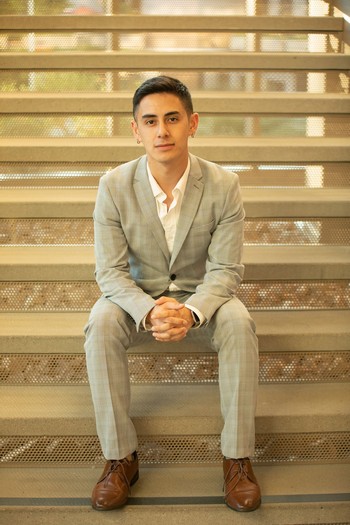

I’ve taken to calling Jonathan Ezequiel Donabo my little brother ever since he signed with our parent publisher, Pronto. I’ve been highly anticipating his book of poetry Nolan since last December, and now that it’s out, I can assure you that it’s everything I was excited for and more. Donabo is an extremely talented writer and his poems have a mix of humor, heart, depth, and realism that hit the reader hard in just a few words and details. Set throughout Los Angeles, Mexico, and the Inland Empire, the Nolan poems tackle life for a family of color in modern-day SoCal with a touch of magical realism in the telling. I took a moment to catch up with Donabo to learn more about Nolan and what the public can expect now that his debut book is finally out in the world.

Nolan is your debut book and the second release from our parent publisher Pronto—congratulations! In addition to being a scholar and a dancer, have you always wanted to be a writer? If so, did you expect your first book to be so vulnerable regarding race, sexuality, and religion?

Looking back in my journals from when I was in middle school/high school, I found that I admired dance way before I started dancing, but I had always been writing—so in some way I felt like I would do both before I knew that it was possible. I started writing more seriously when I was around 14; I think the first poem I wrote, that was for the sake of writing—and not assigned by a teacher, was written after an argument with my mom. I ran out of my house and walked around the neighborhood while writing a poem on my iPod touch. When I came back to my house, I had a poem written and different loose ends.

I want to say I don’t think I expected Nolan to be so vulnerable, but I feel in some way I put a lot of safeguards up for myself to prevent it from being too vulnerable for me. For one, I wrote the collection of poetry mostly in third person—on top of creating a somewhat fictional character. It is comforting to feel I have preserved some level of pseudo-anonymity, even if a lot of my tea is spilled.

After I got to grad school I realized that many of the chicanx/latinx folk that are writing had similar experiences situated in some of the same spaces that Nolan is set in in Socal. I wrote Nolan and the Microscopic Dinosaurs after realizing that my family moved to the IE from LA because of gang violence like so many other Black/Brown folk in the early 2000’s—something I was too young to fully grasp at the time. While this may not have been an experience I expected to share, I do think it is necessary to share to disrupt neat suburban/middle class narratives of becoming that are often presented for racialized queer bodies, and to remind people that LA has more than Beverly Hills and West Hollywood. (Although the fact that it took pursuing doctoral work to have someone assign literature by latinx folk, highlights some of the institutional problems still present in the university system today.)

Though Nolan is a collection of poems, there is a clear narrative that ties the entire book together. Rather than it being a series of poems on a few similar topics, it’s a series of poems following a single character through life and time. Did you ever consider writing Nolan as prose? A short story or novel, maybe?

Though Nolan is a collection of poems, there is a clear narrative that ties the entire book together. Rather than it being a series of poems on a few similar topics, it’s a series of poems following a single character through life and time. Did you ever consider writing Nolan as prose? A short story or novel, maybe?

I love writing prose when it comes to writing essays, but I don’t know if I am capable of writing a novel in the same way. I tried starting to write a novel in high school, and wrote Nolan in college instead. Nolan might have been a novel in some other life.

Similarly, poetry allows the writer to take a bit of a step back from exposition and lengthy explanations—instead you get snapshots of moments in time. Was there a reason behind telling Nolan’s story in this sporadic, somewhat distanced way?

Deleting lines and omitting things was definitely a tool I used throughout Nolan; I wrote many of the poems in traditional form then tore them apart, omitted words, reordered things. I wrote the poems, numbered them (even numbers are contradictory if we think about them long enough), and intentionally took some out to make the story more fragmented and to make it so that the reader can never witness all of Nolan. We are never really able to witness another person’s self in the same way that we do our own, and even then, our own self is always elusive—always escaping our full understanding. Life is tumultuous and I wanted Nolan’s structure to mirror it in some way.

Snapshots of moments in time are all we can bear witness to for the majority, if not all, our experiences. Some experiences affect us more than others and some affect us without us even knowing. Our experiences/memories are so fragmented it requires effort to try and understand each other and ourselves, and yet, we might never fully understand. I think this is where compassion comes into play—not ever fully knowing, but not arguing against people’s pain. I wrote Nolan to learn to be more compassionate to myself.

In your collection, time is not linear. In some poems, Nolan is a child, a young adult, or an adolescent, and in others he’s not even born or seems held in a space post life/death. Do you intend Nolan (the character) to be read as a full person or as more of a concept? Or a little of both? Could he be sort of an “everyman” for kids of color living in the city right now, today?

To me, Nolan is a person and a feeling; but at the same time, I am still trying to figure out who/what Nolan is—so I think you’re right to say that it could be a little bit of both.

I think Nolan as a feeling might answer the “everyman” question. While people of color have a plethora of different/unique experiences, there are some feelings of being on the periphery and the violence that that entails, that I feel many people of color can relate to—I think Nolan begins to engage with/encapsulate some of those feelings. Being on the periphery is unique and wild in that way, because we are never on the periphery of our own lives—everything is felt.

To some people Nolan is totally a person. I had people close to me ask me “How is Nolan doing?” when I was writing the collection, and I would answer candidly hahaha.

It was great to see so many spots around Los Angeles featured in Nolan’s poems and wanderings. For locals, these pieces are especially vivid. In contrast to the poems set in Mexico though, LA has a different type of terror that is pretty on the nose for the country right now: police brutality, death, drugs, and the treatment of people of color in America. Why did you choose LA as the backdrop for these poems? Are the characters of the wider story Nolan, Mexico, and Los Angeles? Or Nolan, Mexico, and America?

I chose LA for some of the poems because it was an experience that I could speak to. LA has, in many ways, been so important to my own coming of age story. Even after my family moved out, we would still go every weekend to visit family and go to church. When I became an adult, LA became my playground in other ways; it was where I started to date and started meeting more queer people.

Mexico, LA, and Riverside are common places where people migrate to and from often. Many of my family members were still in Mexico, so my family would travel back often to visit or stay over the summer. For many first generation latinx folk, the communities that we are part of and care for, are transnational—the nation state can’t hold our bonds with each other. I am not sure if America or Mexico are characters I wrote into the collection specifically, but that’s the fun part of Nolan (and literature in general), it’s meant to be interpreted in different ways.

Sexuality and religion play prominent parts in Nolan, especially from the “coming of age” lens. These themes expose Nolan’s vulnerability in different yet similar ways—Nolan feels abused and played with by God, and he feels unsure of who or what he is in his romantic and sexual encounters with men. How connected are these feelings and themes to you as the author?

I came out pretty early, at around 14, and I lived in and was raised in a Christian household. So I knew a lot about the Bible, and I also knew I was queer. Religion is institutionalized like many other things, and the violence that has been/is enacted by it is always in the background for many people of color, and doubly for queers of color.

When I started dating, I was not so much worried about the religion I was raised with, but with the uncertainty in dating in general. Dating is weird and hard, and requires that you relinquish individual control to some extent—since love and care consists of creating and expanding meaning and identity together. Now, add being queer to that (put religion in the background) and you get some rough experiences hahaha.

Note, there is a difference between the ways we institutionalize religion and the belief in God—though they are closely intertwined. I believe in God, but like many good people, I am mad at God.

What’s next for you and Nolan in the midst of the ongoing pandemic? Are you thinking of doing signings, readings, and other events (virtually or socially distanced) in the near future?

The pandemic has been wild for both Nolan and I. I had planned on doing events here and there in San Diego, LA, and IE, and maybe farther than that if I was asked to. I am feeling mostly settled and used to being inside, so I think people can expect some online readings soon. They can definitely expect some events and soirees after this whole thing is over.

To help Donabo during this difficult time, be sure to grab your own copy of Nolan today and leave a review!